| The Radburn Association |

THE GRANGE TAPES: LOST RADBURN STORIES

Although Radburn was one of the most publicized communities ever founded in America, today some of its history is shrouded in mystery. But tape-recorded interviews with Radburn’s founders and settlers, stored for decades in The Grange, provide missing pieces of our fascinating story. This is part of a series of vignettes about life here almost a century ago.

‘SUICIDE’ HILL: ONCE, NOT SUCH AN EXAGGERATION

Suicide Hill, awaiting the first snowfall

By Rick Hampson

To call the gentle slope at the eastern edge of A Park “Suicide Hill’’ – as have generations of young winter Radburn sledders -- would seem like hyperbole.

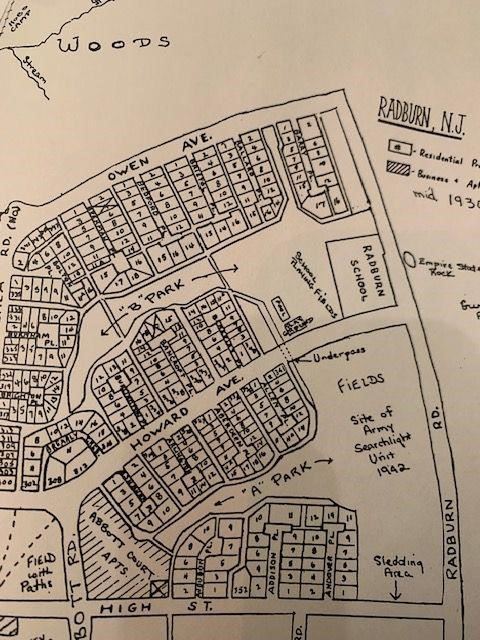

But the name made more sense in the 1930s and ‘40s, before Alden Terrace stood between A Park and Radburn Road; before Radburn’s Andover and Addison places were developed; and before the open fields that surrounded Radburn became housing developments.

In those days, “there was a great big drop when you went out here to Radburn Road,’’ Harriet Roeder of 4 Allen Place recalled in an interview at her home in 1978. ’’The kids used to call it Suicide Hill, because in winter they got out there with their sleds and would go down into the road.’’

By “the road,’’ she may have meant High Street; with the Radburn School at their back and Radburn Road on their left, sledders could ride down the long snowy slope all the way to (and maybe into?) High.

Or Harriet Roeder may have meant Radburn Road itself. In her 2010 history of Fair Lawn, Jane Lyle Diepeveen, who grew up at 10 Bolton Place in Radburn, wrote: “On one side of the hill was a sand cliff where Radburn Road had been cut through. This was the spot for dare-devil jumps with a soft landing.’’

She called the long slope from Howard Avenue o High Street “a perfect hill for sledding.’’

But one day at the beginning of World War II, she recalled, U.S. Army “soldiers appeared on our sledding field and established a base… We had to find another place for sledding.’’

A similar account was offered in an unpublished memoir by Mac Aldrich, who lived on Beekman and Bancroft places as a boy, and who drew the map above.

Wintertime daredevilry was an ironic feature in the model community that first marketed itself in 1929 as “safe for children’’ and systematically separated pedestrians and vehicles. But, as Radburn’s founding designer Clarence Stein conceded in his own memoir, “the spirit of adventure should not be extinguished.’’

Other hills, other thrills

Suicide Hill was one of several Radburn sledding venues in those days.

In another 1978 interview – a recording of which, like the one with Harriett Roeder, was stored for decades in the Radburn Association headquarters in The Grange – Bill Elbow of 3 Audubon Place recalled that kids would sled in winter “behind the telephone building’’ on the south side of Fair Lawn Avenue. The slope was called “Farmer’s Hill’’ (or Farmer Brown’s Hill,’’ according to Ben Russell, who was born in 1933 and lived at 9 Bedford Place).

And there was – and still is -- a beginner’s hill. In her 1999 memoir of Radburn life, Lois Ann Bull, who grew up at 15 Ballard Place, wrote that in B Park, ‘‘the viewing bank for the outdoor stage doubled as the sledding hill. With cold nose and mittened hands, I slogged my way to the top again and again, dragging my red-trimmed Flexible Flyer behind me.’

Radburn’s is hardly the only “Suicide Hill.’’ They exist around the English-speaking world wherever children imagine themselves to be risking life and limb on a sled. The name undoubtedly will become less common, given the growing incidence of suicide and awareness of factors that lead to it.

There is, however, no record of any critical injury on the original Suicide Hill. So Radburn kept its record as “safe for children’’ – even those on speeding sleds.

Contributing: Stephen Taylor

HOW RADBURN'S STREETS GOT THEIR NAMES

If you live on Howard Avenue, you may know your street is named for Ebenezer Howard, founder of the English Garden City movement and Radburn’s ideological godfather.

If you live on Owen, your avenue is named for Robert, the 19th century Welsh industrialist who founded the utopian socialist community of New Harmony, Indiana.

If you live on Burnham Place, your cul-de-sac honors Daniel, the Chicago architect and city planner who famously said, “Make no little plans.’’

But how did the many other avenues, streets and places in Radburn get their names?

Our best evidence comes from Charles Ascher, staff lawyer for the City Housing Corp., which developed Radburn in the late 1920s. In an interview recorded in 1970 and stored ever since at The Grange, Ascher said the street names were selected by himself and Louis Brownlow, Radburn's first project manager.

They did so, Ascher recalled, “one weekend at my place in Sunnyside Gardens (in Queens). … We cooked up the idea of having all the streets on a superblock begin with the same letter, so at least a man coming from outside could be guided. Then, we got names with historical meanings’’ – or, failing that, English ones.

According to the prevailing wisdom, he said, “People like to buy houses on streets that have nice Anglo-Saxon-sounding names.'' (This was gospel in the New York real estate world of CHC founder Alexander Bing. For example, Kew Gardens, the Queens garden suburb, was named for the famous botanical gardens in London.)

He and Brownlow had one other rule, Ascher added: “We decided not to commemorate any living people.’’

Besides the byways mentioned above, here are some other streets and the people or places for which or whom they probably were named.

-

Ruskin Place: John Ruskin, the 19th century British critic and philosopher whose ideas influenced the founders of the Garden City movement, and thus Radburn’s planners, Clarence Stein and Henry Wright.

-

Ballard Place: Edward L. Ballard, a New York insurance executive and associate of John D. Rockefeller Jr., the CHC’s largest single investor. Despite Ascher’s rule against naming streets for the living, Ballard was still breathing when the cul-de-sac’s houses were built circa 1932. But by then Ascher and Brownlow had left the CHC, and the name may have been selected by someone else.

-

Ashburn Place: Charles E. Ashburner, a municipal management pioneer and Brownlow mentor whom Brownlow identified in his autobiography as the first city manager in America.

-

Rutgers Terrace: Henry Rutgers, the Revolutionary War military officer and philanthropist for whom New Jersy’s state university also is named.

-

Brearly Crescent: David Brearly, an American Founding Father and jurist from New Jersey.

-

Sunnyside Drive (no part of which is in Radburn today, but might have been named before City Housing went broke in 1934 and sold much of its land): The CHC’s Radburn-forerunner development in Queens, Sunnyside Gardens.

-

Audubon Place: John James Audubon, the naturalist and ornithologist.

-

Landmark Lane (in The Crossings): Landmark Properties, the original developer of the site once known as Daly Field – itself named for Radburn’s longtime maintenance chief, Charles Daly.

But most of Radburn’s streets, such as Bristol, Bedford, Reading, etc., seem to have been chosen because they’re the names of cities or towns in England -- and thus, to our Yankee ears, sound classy.

Thanks for reading The Radburn Tales by Rick Hampson and Stephen Taylor! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

EARLY RADBURN: A HUNTER'S PARADISE

By Rick Hampson

When Radburn was settled in the late 1920s and early ‘30s, it was surrounded by miles of farms, woods, and fields – and the animals who lived there

Kathy Veile recalled that in hunting season her husband Fred would rise before 6 A.M., get his rifle, and walk east from their Allen Place home in the general direction of the Saddle River.

“He’d come home with two pheasants all the time,’’ she recalled in an interview that was recorded in 1978 and stored ever since at the Radburn Association offices in The Grange building.

Cathy Roeder, who grew up on Allen, said in another interview that some of her friends in Radrock Estates, the development constructed across Radburn Road in the early 1940s, “had to wear red in fall, because there were hunters out.’

In fact, at a Radurn Citizens Association meeting around the same time, a resident rose to ask that Radburn property be posted: NO HUNTING

THE GRANGE TAPES: BE TRUE TO YOUR SCHOOL

By Rick Hampson

Virgil Sasso never forgot his first Fair Lawn-Ridgewood football game.

It was Thanksgiving 1944, and he had just moved from Pennsylvania to teach at Fair Lawn High School, which had opened the previous year.

Nothing prepared him that day for the sound of kids from Radburn rooting for Ridgewood High School, nor the sight of several Radburn boys playing for Ridgewood.

Sasso soon learned the explanation for this apparent treason.

Before the opening of Fair Lawn High, the borough sent its young to three high schools -- Paterson East Side, Hawthorne and Ridgewood. Most Radburn students attended Ridgewood (and for a time the Radburn Association helped pay their out-of-district tuition, which was higher than the East Side rate.)

When Fair Lawn High opened in 1943, borough students already enrolled in the other high schools were allowed to stay through graduation. Hence, some of the Fair Lawn kids in the Ridgewood camp at the Thanksgiving game were simply being true to their school.

Consider the example of Betty Reyle, who grew up on Allen Place and Ramapo Terrace in Radburn. In 1944 she graduated from Ridgewood High, where she’d met the fellow who the following year she would marry. He was from Radrock Estates -- Glen Rock also in those days sent its high schoolers to Ridgewood.

In an interview recorded in 1978, Sasso said that tensions between Radburn and the rest of Fair Lawn stemmed in part from the fact that most Radburn kids went to high school in Ridgewood, while most other Fair Lawn students went to East Side.

Another reason for what he termed the intra-borough “hostility,’’ was that “people in Radburn were more progressive, if that’s the word. … Radburn had a sewer system when Fair Lawn didn’t. Radburn had parks and pools.’’ As a teacher, he heard students say things they’d heard from their parents, like “Radburn people think they’re better.’’

“When I got to know Radburn people, that wasn’t true at all,’’ Sasso said. He added: “I never remember any hostility on the part of Radburn people against Fair Lawn.’’

Radburn residents, he said, “wanted things better and were willing to spend the money.’’ Fair Lawn voters, in contrast, had helped defeat a proposed high school a decade earlier, despite the promise of federal assistance. Many residents, Sasso said, “seemed to be very proud people – they didn’t want a government hand out.’’

Eventually, “the high school was built because of the pressure of the Radburn people,’’ and the school helped unify the borough, he said.

At the recommendation of another teacher, he moved to Radburn, eventually buying a house on Brearley Crescent and serving as a Radburn trustee for five years. He became vice principal and athletic director of Fair Lawn High, whose football field is named for him.

Asked in 1978 if he’d ever leave Radburn, he said no. For one thing, “If I left Radburn, I’d have to leave my wife.’’

Rick Hampson and Steve Taylor offer free walking tours of Historic Radburn. For information contact Rick at fjhampson@gmail.com or call/text 201 286 9577.

RADBURN’S GRANGE: ‘CITADEL’ OF A RURAL PAST

By Rick Hampson

Radburn’s current discussion about the future of the Grange revives an old topic. Calls for a community recreation center – and concerns about its cost – are almost as old as Radburn itself.

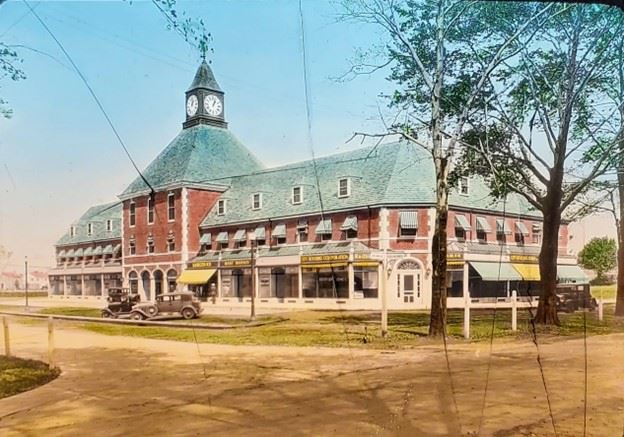

In the 1930s, the new community had even more group activities than now. Most took place on the upper floors of the Plaza Building or in the Grange Hall, which had been purchased by the City Housing Corp. (Radburn’s developer) in early 1929.

The hall, which a local newspaper called the “citadel of rural Fair Lawn,’’ was built in 1909. It housed the local chapter of the Grange, a national farmers’ organization formed in 1867 to promote its members’ economic and social well-being.

After its purchase by the CHC, the Grange Hall was converted into Radburn’s “Activity Center.’’ (See photo above.) The second floor (today’s club room) was converted into a low-ceilinged gym for “basket-ball,’’ with showers downstairs, according to minutes of a March, 1930, Board of Trustees meeting.

In interviews tape recorded in the late 1970s, several early Radburn residents recalled how cold the building was in winter -- for basketball or anything else. But Radburn’s manager told the Trustees that while the gym was “temporary in character and inadequate in size,’’ it was well used.

Hoopsters weren’t the only ones looking for indoor play space. The Radburn Players reported in 1930 that at their last production – staged in the Plaza Building -- “people in the rear seats of the auditorium could not see the stage.’’

The solution seemed to be a new “community house.’’ At a Citizens’ Association meeting on April 7, 1931, a committee was tasked with preparing cost estimates for such a facility – despite the advent of the Depression, which began with the stock market crash about 18 months earlier.

In a letter to the Trustees, the CA committee reported that a poll of residents determined that a majority were willing to purchase bonds worth up to $15,000 to help finance such a center.

Alexander Bing, chairman of the City Housing Corp., was a Trustee. Although by this time he privately believed that the Depression had fatally wounded his plans for a bigger Radburn, he – shrewdly perhaps, if he was trying to put the brakes on an expansive proposal – offered assistance in formulating cost estimates.

The Depression worsened, and the community house idea seems to have faded.

In 1942, a Citizens Association committee that studied the cost of a community center concluded it was “out of proportion’’ to Radburn’s financial capacity, and recommended creation of a special fund for its future construction. The Trustees did so.

In November, 1946, the company that had emerged from the CHC’s 1934 bankruptcy announced it would stop mortgage payments (to the Fair Lawn Grange) on the Grange Hall. The Radburn Association stepped in to buy the building for about $6,000. Radburn paid in part – with the blessing of the Citizens Association – by tapping the Community House Fund, while promising to replenish it or pay it back.

And the community house idea did not die. In 1949 a special Trustees committee studied the building, financing and operation of such a facility.

But the community seems to have been of two minds on whether the Grange should be the community center, or whether a new one should be constructed. In 1951, the Trustees voted to both commission plans for a Grange addition/renovation and to proceed on plans for a community house.

For some reason only the Grange project moved forward, and on Jan. 19, 1953, the renovated and expanded Radburn Grange Hall officially opened. It contained the association offices and the Radburn Library; an addition (behind the original hall) contained a gym, stage, and space for a nursey school.

And the notion of a “community house’’ -- so important to early Radburn residents -- seems to have been forgotten.

Contributing: Stephen Taylor

‘GO PLAY IN THE STREET’

By Rick Hampson

One of the most famous unintended consequences of the Radburn Plan is children’s insistence on playing in the cul-de-sacs, which were designed to accommodate vehicles and exclude pedestrians – especially kids.

One of Radburn’s key marketing slogans was “Safe for Children.’’ But before the community was built, its two planners were warned about children’s insistence on literally playing in traffic.

Before completing their plan for Radburn in 1928, Clarence Stein and Henry Wright consulted all sorts of experts, including the National Recreation Association.

The group’s founder and chairman was a Boston philanthropist and lawyer named Joseph Lee (1862-1937), who helped found the 20th Century ‘‘playground movement’’ by buying and clearing slum lots and installing recreational equipment.

Charles Ascher, lawyer for the company that built Radburn, was at Stein and Wright’s meeting with Lee in New York City. In a 1978 interview that was tape-recorded and stored for decades in The Grange, Ascher said Lee listened carefully to a presentation by Stein and Wright. Then he said: ‘‘It is very interesting, your playgrounds and parks. But I have a feeling that the children are going to want to play in the paved areas’’ – the cul-de-sacs.

That, said the crusty old Brahmin, “is where you can bounce a ball, where you can roller skate. It’s where the action is!’’

Ever since, the kids of Radburn have been proving his point.

Stein himself came to acknowledge it. “The sense of exploration and curiosity leads youngsters into forbidden places’’ – the cul de sacs, he wrote in his book Toward New Towns for America.

He went on: “I have studied the reasons for this so that in the future we might keep children and autos apart to an even greater degree.’’ But, he added, “we never will do so completely. … The spirit of adventure must not be extinguished. “

Parents grasped that from the beginning. Since most Radburn kitchens face the cul de sac, an adult working there can keep a direct eye on those at play. And the cul de sacs are safe – it appears that no pedestrian ever has been killed by a vehicle in one of the lanes.

Even the most cautious parents admit their safety.

One day in the last decade of the last century, a boy whose family lived on Bristol Place was constantly underfoot in the busy kitchen. In exasperation, his mother finally snapped, “Nick, go play in the street!’’

Rick Hampson and Steve Taylor lead walking tours of Historic Radburn. For information, contact fjhampson@gmail.com or text 201 286 9577.

RADBURN’S FIRST TOT LOT

Robert Hudson, Radburn’s first recreation director, wrote the first book about the model community. Radburn: A Plan of Living, published in 1934, has everything from how many residents had attended college (about 80 percent) to the number of books in the association’s library (5,400).

But Hudson was not infallible. In an interview recorded in 1978 and stored ever since at The Grange, he wrongly claimed to have invented the word “tot lot.’’

In the summer of 1931, he said in the interview, “we organized a preschool playground activity’’ program in the fenced yard of an old farmhouse on Fair Lawn Avenue called the Children’s House that housed the Radburn Nursery School.

“The question was ‘What do you call it?’’’ Hudson said of the playground. He continued: “One of the very few words I ever coined in my life was ‘Tot Lot.’ … There’s Tot Lots all over the country now. I’m sorry I didn’t register it.’’

Other Radburn residents interviewed in 1978 agreed that Radburn invented the term, though credited Betty Christie, director of the nursery school.

But while Radburn was an early adopter of the Tot Lot name and concept, it was not the first.

On July 15, 1929, for instance, a news wire service story from Philadelphia began:

“Totlot!

It’s a new magic word.

It means rest for mothers.

It means rest for babies.

It means safety for all.’’

That city’s first “totlot” had been created by the Philadelphia Playground Association, a private charitable organization dedicated to improving the lives of poor children. The article reported that similar places existed in Chicago, where they were called “baby playgrounds.’’

The article defined a totlot as an area 18 by 50 feet with a low fence, shower, toilets, sandboxes, swings, jungle gyms and this unique feature: a top bar at the entrance to keep older kids out.

Radburn’s Tot Lot opened June 5, 1931, in what had been the Bogert homestead on the south side of Fair Lawn Avenue, near an approach to the footbridge over the avenue. At the time Hudson told reporters that it was “probably the first playground of its kind’’ for 2-year-olds, and that Radburn was “frankly experimenting.’’

He may have been referring to the fact that Radburn had not just a playground but a supervised program -- six days a week from 8 AM to noon. In his book, he claimed that in summer, it “released 9,000 hours to 70 mothers.’’

Ott in Tot Lot

In 1939, Radburn’s Tot Lot was the scene of a publicity stunt camouflaged as a scientific experiment orchestrated by the New York Herald Tribune.

New York Giants baseball star Mel Ott agreed to mimic the activities of a 4-year-old – Johnny Beckett of Bancroft Place – to determine if an adult, even a trained athlete, could follow “a little tot around and go through all the physical activities that the child does, without fading.’’

Mel duly shadowed Johnny, swinging, climbing, jumping, riding and even playing ball. The Herald Tribune story declared Johnny the winner “hands down.’’ But the Bergen Evening Record, whose story was headlined “Mel Ott Cavorts with Boy,’’ emphasized the man’s endurance.

In fact, Ott that day returned to New York and played both ends of a doubleheader at the Polo Grounds.

Two Tot Lots

In the summer of 1946, the first after World War II, Radburn’s summer recreation program had record participation, including average daily Tot Lot attendance of 150.

But the following year the developer of an apartment complex on Fair Lawn Avenue bought and tore down the Bogert house. So in the summer of 1947, Radburn opened two Tot Lots – one in B Park and one in R Park. They’ve remained there ever since.

As for Johnny Beckett and Mel Ott: the latter died in 1958 in his native Louisiana from injuries suffered in a car crash. He was 49. And the boy with whom the slugger once cavorted died in 2012 in Irving, Texas. He was 77. To his dying day he loved soccer, in which you never stop moving.

THE GRANGE TAPES: TUNNEL FOR RENT

By Rick Hampson

When the Radburn Plaza Building was being built in 1928-29, the cupola for the top of what would become its famous clocktower was fabricated in New York, somewhere east of the East River. For reasons lost to history, it could not be transported to Radburn via rail or barge.

In a recording of a 1969 interview stored for decades in the Grange, Radburn’s first manager, John O. Walker, described the solution to this problem.

The Holland Tunnel, the first vehicular tunnel under the Hudson, had opened in late 1927. In those days, it had almost no overnight traffic.

So the City Housing Corporation, Radburn’s developer, rented the tunnel for a night, allowing the cupola to be trucked under the river and met by a police escort in Jersey City.

It was hauled to Radburn, where – along with another tunnel (the one linking A and B parks) – the cupola would become a symbol of the “town for the motor age.’’

It was not the last time the Holland Tunnel would be closed for such a purpose, but it may have been one of the first. And according to Walker, the fee the Port Authority charged was a relative bargain: $50.

Rick Hampson and Steve Taylor lead free walking tours of Historic Radburn. For information, email fjhampson@gmail.comor call/text 201 286 9577.

JEWS IN RADBURN: HERE FROM THE START

Here’s the conventional wisdom: At least until World War II, Radburn excluded Jews. In the earliest days, the story goes, Jews were turned away as home buyers; and even in later years some real estate agents told Jews, “You’d be more comfortable somewhere else.’’

But interviews with some of Radburn’s founders and settlers, tape-recorded a half century ago and stored ever since at The Grange, tell a different story: Some of the earliest residents were Jewish, and discrimination may have had as much to do with class as religion.

Early Radburn did not welcome all comers. African Americans, for example, were systematically excluded (as they were from almost every other middle-class suburb).

Jews were different. The family of Robert Cohen, an accountant, were the first residents of 5 Aberdeen Place in 1930. Around the same time, the family of Abraham Platt, a stockbroker, became the first residents of 22A Townley Road. A few years later they moved to 10 Ashburn Place.

Around the same time, William Elbow and his wife (a Christian) moved to Radburn from Paterson, where he managed a department store; he’d been told Ridgewood was unwelcoming to Jews. (In 1942, he was elected president of the Radburn Board of Trustees.)

Maxwell Golburgh was a salesman for the City Housing Corp., the company that built Radburn and sold homes here until it went bankrupt in 1934. Golburgh himself bought a home on Owen Avenue in 1948.

Yet some Jews were discriminated against, according to taped interviews with several non-Jewish residents.

Here’s Karl Duerr of 10 Burnham Place, who was a trustee, in 1978: “In the early days, City Housing discriminated. If you were Jewish, you didn’t have much chance of getting in here. You had to fill out a questionnaire to come in. … What faith you were; where you were born; where were your parents born. … They really had the lowdown on you.’’ That stopped, he said, after City Housing went bust.

Lloyd Kerr, another former board member, said that “Mr. (Max) Golburgh was Jewish; he wouldn’t rent to Jewish people.’’ But Kerr, who was a client and an admirer of Golburgh, said the realtor had a motive: “He was trying to keep boorish people away. (It) had nothing to do with religion. He was being selective.’’

(Jane Lyle Diepeveen, a Radburn resident and local historian, wrote in 2010 that Goldburgh told her he’d “made it a point” to sell homes to two Jewish families.)

The man with the most say about who could move into Radburn was its first manager, Major (US Army Ret.) John O. Walker, a courtly Virginian born two decades after the end of the Civil War.

In 1969, he confirmed that prospective residents had to fill out a questionnaire and be interviewed: “Before we signed (potential residents) up, we compared them to people here -- to figure if they could get along together. And if we decided they couldn’t do it, we turned them down.’’

He continued: “Take for example, Bob Cohen, one of the first Jews that bought a place here. … Any other Jews that came around to apply, we compared them to Bob Cohen, and figured that if they couldn’t get along with Bob Cohen, they couldn’t get along with anybody. So out they went.’’

Cohen was an accountant – a professional, like most of his neighbors. But a Jewish factory worker with an eighth-grade education probably was not welcome in Radburn.

In his Radburn history Garden Cities for America, Daniel Schafer concluded that while early “Radburn followed no explicit policy of discrimination … realtors hired by the CHC discouraged Jews as well as blacks ... to create what they saw as a congenial environment.’’

For Major Walker, at least, life in Radburn was broadening. He was the Platts’ neighbor on Ashburn Place.

One fall, Walker was in the Meyer Brothers department store in Paterson when he noticed a selection of greeting cards, including some for Rosh Hashanah. Walker had never even heard of the Jewish holidays, let alone cards for them.

“And I thought it would be a very nice thing to give Abe Platt a Jewish New Year’s card, which I did. And he was very appreciative and surprised to get it, and said it was the only time he’d gotten a Jewish New Year’s card from a gentile.

“As a result of that, up to the present time, that’s 40-odd years, I have never missed sending Able Platt a Jewish New Year’s card. He lives now in Arizona, retired, and I’ll get him another one October 1 of this year.’’

A, B … R? THE ALPHABETIC LOGIC OF RADBURN’S STREETS

Generations of Radburn residents, noting that two groups of streets north of Fair Lawn Avenue begin with A or B, and that a group on Southside begins with R, have wondered: What about the alphabet in between?

That question had long bugged former Radburn trustee Fred McMullen. But in 1969, he got an answer.

It came in his interview with Charles Ascher, the lawyer for the company that developed Radburn and the man who named Radburn and its streets.

Ascher noted that Radburn was developed simultaneously north and south of Fair Lawn Avenue, with two “superblocks’’ taking shape in the former and one in the latter.

Ascher explained that the CHC had big expansion plans for Northside, where “we hoped we’d build C and D and E blocks,’’ each centered on a park. Accordingly, he said, “We wanted to leave room’’ in the alphabet for expansion toward Glen Rock and the Saddle River.

On Southside, the emerging R superblock also was supposed to be the first of several, because Radburn hoped to attract industry on that side of the community and would need worker housing -- preferably in walking distance. There would be other superblocks, with streets beginning in S, T, etc.

Of course, none of that came to pass. The Depression killed the market for new single-family homes on Northside, and industry never showed much interest in Radburn. Hence the gap between B and R.

However, just before and after World War II some developers who built on land outside Radburn once owned by the original development company picked up on the alphabetic naming scheme. And so many streets north of Fair Lawn Avenue that are not in the Radburn Association begin with F, G and H – even though their residents can’t use the pools.

Radburn’s first night: Allen Place 1929

Radburn’s very first settlers were Jim and Emma Wright of Paterson, who moved into 2 Allen Place on April 25, 1929. Two days later, they got company: Howard and Lillian Zeller at 14 Allen, and Fred and Kathy Veile at #8.

Although the Wrights moved in first, there was no agreement on who was second -- the Veiles or the Zellers. “We used to argue about who got there first,’’ Kathy Veile recalled in 1978. “We always said our moving van passed the Zellers’’ en route to Allen.

Kathy -- by then a widow for two decades -- recalled the three couples’ first night on the unfinished, isolated cul de sac, surrounded by woods and fields and the beginnings of a construction site.

“We all went to the Wrights’ house and became acquainted,’’ she said. Beverages were consumed. And, as a lark, Kathy said, “We elected Jimmy Wright mayor, Howard Zeller chief of police and Freddy the fire chief.’’

(In fact, Jim Wright would become the first resident on the Board of Trustees.)

It was the beginning of an exciting time. As Kathy put it, “You felt like you were pioneering. It was an interesting little community to start, and we all felt that we started it, that we were very important people. We went to meetings every night on every little subject, and used to fight like cats and dogs, and end up best friends.’’

PARTY TOWN FOR THE MOTOR AGE

An exceptionally high percentage of residents of early Radburn had attended or graduated from college, and some residents have said the place felt like a college campus.

But college isn’t all work – then or now – and it seems another side of campus life was reflected in the new community.

“The first people who came here were partying types,’’ Karl Duerr of 10 Burnham Place said in an interview in 1978. “Every Saturday night was a gala affair. If you went to bed to sleep you were wasting your time, because they were hollering and hooting and carrying on until the wee small hours.’’

When Lloyd Kerr, a former president of the Board of Trustees, was asked in 1978 about residents who exchanged houses, he replied that they also were “exchanging their spouses.’’

“That was Prohibition,’’ he said, and among ‘’the young people who were living here …. it was considered smart to get booze and get a little cockeyed. A lot of marriages were broken up just because of that idiocy.’’

Community social events were boisterous. Robert Turner, Radburn’s second manager, recalled that dances sponsored by groups such as the Bridge Club and the Fire Company were very popular. “Although there were many stories about these functions,’’ he said, “the general rule was ‘hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil.’’’

But the Depression, which followed the stock market crash of October 1929, put a damper on the festivities – sort of.

“We couldn’t have parties, so we had something called a ‘Depression Party,’’’ recalled Harriet Roeder, who moved with her husband Bill to Allen Place in 1929. “You’d invite a bunch of people who’d bring whatever they had. … Everybody brought (some kind of alcohol) and dumped it into the punch bowl. How we survived, I don’t know!’’

But eventually even Radburn’s partying spirit was dampened by economic reality. Many of the biggest partiers “went broke and had to leave,’’ Duerr said. “So things quieted down around here quite a bit.’’